Introduction

and Overview:

Recasting

the Middle East

Men are the

managers of the affairs of women

for that God

has preferred in bounty

one of them

over another ....

And those

you fear may be rebellious

admonish;

banish them to their couches,

and beat

them. --Quran,

Sura 4, verse 38

God . . .

makes it the duty of the man to provide all economic means for (his wife) . . .

. And in exchange for this heavy responsibility, that is, the financial burden

of the woman and the family, what is he entitled to expect of the woman? Except

for expecting her companionship and courtship, he cannot demand anything else

from the woman. According to theological sources, he cannot even demand that she

bring him a glass of water, much less expect her to clean and cook

--Fereshteh

Hashemi, Iranian Islamist intellectual, 1980

The study of social change has tended to regard certain

societal institutions and structures as central and then to examine how these

change. Family structure, the organization of markets, the state, religious

hierarchies, schools, the ways elites have exploited masses to extract surpluses

from them, and the general set of values that governs society's cultural outlook

are part of the long list of key institutions. In societies everywhere, cultural

institutions and practices, economic processes, and political structures are

interactive and relatively autonomous. In the Marxist framework, infrastructures

and superstructures are made up of multiple levels, and there are various types

of transformations from one level to another. There is also an interactive

relationship between structure and agency, inasmuch as structural changes are

linked to "consciousness"--whether this be class consciousness (of

interest to Marxists) or gender consciousness (of interest to feminists).

Social change and societal

development come about principally through technological advancements, class

conflict, and political action. Each social formation is located within and

subject to the influences of a national class structure, a regional context, and

a global system of states and markets. The world-system perspective regards

states and national economies as situated within an international capitalist

nexus with a division of labor corresponding to its constituent parts--core,

periphery, and semiperiphery. As such, no major social change occurs outside of

the world context.' Thus, to understand the roles and status of women or changes

in the structure of the family, for example, it is necessary to

examine economic development and political change, which in turn are affected

by regional and global developments. As we shall see in the discussion of

women's employment, the structural determinants of class location, state legal

policy, development strategy, and world market fluctuations come together to

shape the pace and rhythm of women's integration in the labor force and their

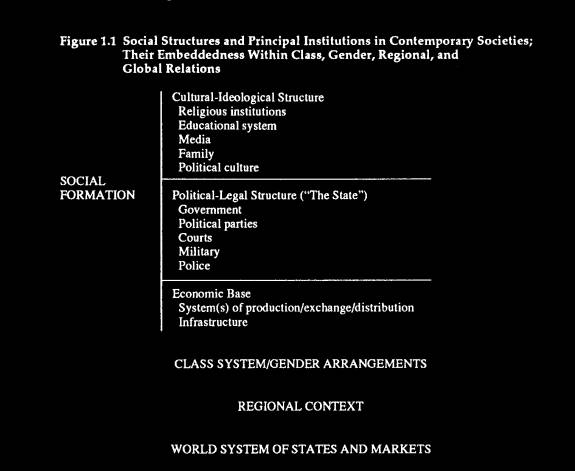

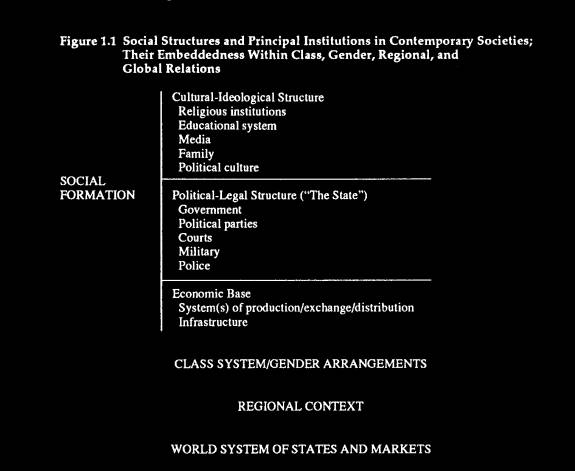

access to economic resources. Figure 1.1 illustrates the institutions and

structures that affect and arc affected by social changes in a Marxist inform

ed world system perspective. The institutions arc embedded within a class

structure (the system of production, accumulation, and surplus distribution),

a set of gender arrangements (ascribed roles to men and women through custom or

law; cultural understandings of "feminine" and "masculine"),

a regional context (the Middle East, Europe. Latin America), and a world system

of states and markets characterized by asymmetries between core, periphery, and

semi-periphery countries.

Social change and societal

development come about principally through technological advancements, class

conflict, and political action. Each social formation is located within and

subject to the influences of a national class structure, a regional context, and

a global system of states and markets. The world-system perspective regards

states and national economies as situated within an international capitalist

nexus with a division of labor corresponding to its constituent parts--core,

periphery, and semiperiphery. As such, no major social change occurs outside of

the world context.' Thus, to understand the roles and status of women or changes

in the structure of the family, for example, it is necessary to

examine economic development and political change, which in turn are affected

by regional and global developments. As we shall see in the discussion of

women's employment, the structural determinants of class location, state legal

policy, development strategy, and world market fluctuations come together to

shape the pace and rhythm of women's integration in the labor force and their

access to economic resources. Figure 1.1 illustrates the institutions and

structures that affect and arc affected by social changes in a Marxist inform

ed world system perspective. The institutions arc embedded within a class

structure (the system of production, accumulation, and surplus distribution),

a set of gender arrangements (ascribed roles to men and women through custom or

law; cultural understandings of "feminine" and "masculine"),

a regional context (the Middle East, Europe. Latin America), and a world system

of states and markets characterized by asymmetries between core, periphery, and

semi-periphery countries.

The study of social change is also often done comparatively. Although it

cannot be said that social scientists have a single, universally recognized

"comparative method," some of our deepest insights into society and

culture are reached in and through comparison. In this book, comparisons among

women within the region will be made, and some comparisons will be made between

Middle Eastern women and women of other Third World regions. Indeed, as a major

objective of this book is to show the changing and variable status of women in

the Middle East, the most effective method is to study the subject

comparatively, emphasizing the factors that best explain the differences in

women's status across the region and over time.

Yet such an approach is rarely applied to the Middle East,

and even less so to women in Muslim societies in general.²

The Debate on the Status of Arab-Islamic

Women

That women's legal status and social positions are worse in

Muslim countries than anywhere else is a common view. The prescribed role of

women in Islamic theology and law is often argued to be a major determinant of

women's status. Women are perceived as wives and mothers, and gender segregation

is customary, if not legally required. Whereas economic provision is the

responsibility of men, women must marry and reproduce to earn status. Men,

unlike women, have the unilateral right of divorce; a woman can work and travel

only with the written permission of her male guardian; family honor and good

reputation, or the negative consequence of shame, rest most heavily upon the

conduct of women. Through the Shari'a, Islam dictates the legal and

institutional safeguards of honor, thereby justifying and reinforcing the

segregation of society according to sex. Muslim societies are characterized by

higher-than-average fertility, higher-than-average mortality, and rapid rates of

population growth. It is well known that age at marriage affects fertility. An

average of 34 percent of all brides in Muslim countries in recent years have

been under twenty years of age, and women in Muslim nations bear an average of

six children.

The Muslim countries of the Middle

East and South Asia also have a distinct gender disparity in literacy and

education, as well as low rates of female labor force participation.3 In 1980

the proportion of women to men in the paid labor force was lowest in the Middle

East (29 percent, though not far behind Latin America) and highest in Eastern

Europe and the Soviet Union, where the proportion was 90 percent.4

High fertility, low literacy, and low labor force participation are

commonly linked to the low status of women, which in turn is often attributed to

the prevalence of Islamic law and norms in Middle Eastern societies. It is said

that because of the continuing importance of values such as family honor and

modesty, women's participation in nonagricultural or paid labor carries with it

a social stigma, and gainful employment is not perceived as part of their roles

Muslim societies, like many others,

harbor illusions about immutable gender differences. There is a very strong

contention that women are different beings--different often meaning inferior--which

strengthens social barriers to women's achievement. In the realm of education

and employment, not only is it believed that women do not have the same

interests as men and will therefore avoid men's activities, but also care is

exercised to make sure they cannot prepare for roles considered inappropriate.

Women's reproductive function is used to justify their segregation in public,

their restriction to the home, and their lack of civil and legal rights. As both

a reflection of this state of affairs and a contributing factor, very few

governments of Muslim countries have signed or ratified the United Nations

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Half

of the forty-nine countries that have not signed have large Muslim populations.

In many Muslim countries, where gender inequality exists in its most egregious

forms, it claims a religious derivation and thus establishes its legitimacy.

Is the Middle East, then, so

different from other regions? Can we understand women's roles and status only in

terms of the ubiquity of deference to Islam in the region? In fact, such

conceptions are too facile. It is my contention that the position of women in

the Middle East cannot be attributed to the presumed intrinsic properties of

Islam. It is also my position that Islam is neither more nor less patriarchal than other major

religions, especially Hinduism and the or ear two Abrahamic religions, Judaism

and Christianity, all of which share the view of woman as wife and mother.

Within Christianity, religious s omen continue to struggle for a position equal

with men, as the ongoing debate over women priests in Catholicism attests. In

Hinduism a potent female symbol is that of the sari, the self immolating

widow. And the Orthodox Jewish law of personal status bears many similarities to

the fundamentals of Islamic law, especially with respect to marriage and

divorce. The gender configurations that draw heavily from religion and

cultural norms to govern women's work, political praxis, and other aspects of

their lives in the Middle East are not unique to Muslim or Middle Eastern

countries.

Religious-based

law exists in the Middle East, but not exclusively in Muslim countries; it is

also present in the Jewish state of Israel. Rabbinical judges are reluctant to

grant women divorces, and, as in Saudi Arabia, Israeli women cannot hold public

prayer services. The sexual division of labor in the home and in the society is

largely shaped by the Halacha, or Jewish law, and by traditions that continue to

discriminate against women. Marital relations in Israel, governed by Jewish law,

determine that the husband should pay for his wife's maintenance, while she

should provide household services. According to one account, "The structure

of the arrangement is such that the woman is sheltered from the outside world by

her husband and in return she adequately runs the home. The obligations one has

toward the other are not equal but rather based on clear gender

differentiation."6

Neither are the marriage and fertility patterns mentioned above unique to

Muslim countries; high fertility rates are found in sub-Saharan African

countries today and were common in Western countries in the early stage of

industrialization and the demographic transition. The low status accorded

females is found in non-Muslim areas as well. In the most patriarchal regions of

West and South Asia, especially India, there are marked gender disparities in

the delivery of health care and access to food, resulting in an excessive

mortality rate for women. In northern India and rural China, the preference for

boys leads to neglect of baby girls to such extent that infant and child

mortality is greater among females; moreover, female feticide has been well

documented. Thus, the low status of women and girls is a function not of the

intrinsic properties of any one religion but of kin-ordered patriarchal and

agrarian structures.

Finally, it should be recalled that in all Western

societies women as a group were disadvantaged until relatively recently.8

Indeed, Islam provided women with property rights for centuries while women in

Europe were denied the same rights. In

India, Muslim property codes were more progressive than English law until the

mid-nineteenth century. It should be stressed, too, that even in the West there

are marked variations in the legal status, economic conditions, and social

positions of women. The United States, for example, compares poorly to

Scandinavia and Canada in terms of social policies for women. Why Muslim women

lag behind Western women in legal rights, mobility, autonomy, and so forth, has

more to do with developmental issues--the extent of urbanization,

industrialization, and proletarianization as well as the political ploys of

state, managers with religious and cultural factors.

Gender asymmetry and the status of

women in the Muslim world cannot be solely attributed to Islam because adherence

to Islamic precepts and the applications of Islamic legal codes differ

throughout the Muslim world. For example, Tunisia and Turkey are secular states,

and only Iran has direct clerical rule. Consequently, women's legal and social

positions are quite varied, as this book will detail. And within the same Muslim

society there are degrees of sex-segregation, based principally on class. Today

upper class women have more mobility than lower-class women, although in the

past it was the reverse: Veiling and seclusion were upper-class phenomena. By

examining changes over time and variations within societies and by comparing

Muslim and non-Muslim gender patterns, one recognizes that the status of women

in Muslim societies is neither uniform nor unchanging nor unique.

Assessing Women's Status

In recent years the subject of women in

the Middle East has been tied to the larger issue of Islamic revival, or

"fundamentalism," in the region. The rise of Islamist movements in the

Middle East has once again reinforced stereotypes about the region, in

particular the idea that Islam is ubiquitous in the culture and politics of the

region, that tradition is tenacious, that the clergy have the highest authority,

and that women's status is everywhere low. How do we begin to assess the status

of women in Islam or in the Middle East? Critics and advocates of Islam hold

sharply divergent views on the utter. One author ha sardonically classified much

of the literature on the status of women as representing either "misery

research" or "dignity research." The former focuses on the

utterly oppressive aspects of Muslim women's lives, while the latter seeks to

show the strength of women's positions in their families and communities. In

either case, it is the status of women in Islam that is being scrutinized. Leila

Ahmed once concluded that Islam is incompatible with feminism--even with the,

am/modernist no ion of women's rights-because Islam regards women as the weak

and inferior sex Freda Hussein has raised counterarguments based on the concept

of "complementarily of the sexes" in Islam. Mernissi and others,

although critical of the existing inequalities, have stressed that the idea of

an inferior sex is alien to Islam, that because of their "strengths"

women, had to be subdued and kept under control.9

As noted by the Turkish sociologist Yakin Erturk,

these arguments draw attention to interesting and controversial aspects of the

problem, but they neither provide us with consistent theoretical tools with

which to grasp the problem of women's status nor guide us in formulating

effective policy for strategy and action. They are either highly ethnocentric in

their critique of Islam or too relativistic in stressing cultural specificity.

The former approach attributes a conservative role to Islam, assuming that it is

an obstacle to progress whether it be material progress or progress with respect

to the status of women. Erturk argues that overemphasizing the role of Islam not

only prevents us from looking at the more fundamental social contradictions that

often foster religious requirements but also implies little hope for change,

because Islam is regarded by its followers as the literal word of God and

therefore absolute. The cultural relativist approach produces a circular

argument by uncritically relying on the concept of cultural

variability/specificity in justifying Islamic principles. Erturk notes that many

Western observers who resort to relativism in their approach to Islam hold

liberal worldviews and treat Islamic practices within the context of individual

freedom to worship; any interference with that freedom is seen as a violation of

human rights. But gender tends to become occluded by this preoccupation with the

human rights of cultural groups. As for the Muslim thinkers, a relativist stand

is essentially a defensive response and imprisons its advocates in a pseudo-nationalistic

and religious pride.10

However, as stated earlier, one

premise of this book is that Islam is neither more nor less patriarchal than the

other major religions. Moreover, Islam is experienced, practiced, and

interpreted quite differently over time and space. The Tunisian sociologist

Abdelwahab Bouhdiba convincingly shows that although the Islamic community

considers itself unified, Islam is fundamentally "plastic," inasmuch

as there are various Islams--Tunisian, Iranian, Malay, Afghan, Nigerian, and so

on. » Thus, in order to understand the social implications of Islam, it is

necessary to look at the broader sociopolitical and economic order within which

it is exercised. As Erturk correctly observes, and as can be discerned from the

two contrasting quotes at the beginning of this chapter, whether or not the

content of the Quran is inherently conservative and hostile toward women is

relevant, but it is less problematic than it is made out to be.

An alternative to the conceptual

trap and political problem created by the devil of ethnocentrism and the deep

blue sea of cultural relativism needs to be developed. In this regard it is

useful to refer to various "universal declarations" and conventions

formulated within the United Nations and agreed upon by the world community. For

example, the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (of 1948) provides for both

equality between women and men and freedom of religion. The practical meaning of

gender equality and means to achieve it have been reflected in the United

Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against

Women, adopted on December 10, 1979. The Convention entered into force in 1981

and by July 1992 had 114 government signatories. Similarly, the type of actions

necessary to achieve equality by the year 2000 are set out in the Nairobi

Forward-looking Strategies adopted by the United Nations General Assembly

by consensus in 1985, at the end of the World Decade on Women. While the

Strategies are not legally binding, they reflect a moral consensus of the

international community and provide an understanding of how equality should be

interpreted in practice. The Strategies strongly emphasize the necessity of

fully observing the equal rights of women and eliminating de jure and

de facto discrimination. They address in particular social, economic,

political, and cultural roots of de facto inequality. The Strategies provide a

set of measures to improve the situation of women with regard to social

participation, political participation and decision making, role in the family,

employment, education and training, equality before the law, health, and social

security.

The Universal Declaration on Human

Rights, the Convention, and the Strategies are all intended to set out

universally agreed-upon norms. They were framed by people from diverse cultures,

religions, and nationalities and intended to take into account such factors as

religion and cultural traditions of countries. For that reason, the Convention

makes no provision whatsoever for differential interpretation based on culture

or religion. Instead, it states clearly in Article 2 that "States Parties .

. . undertake . . . to take all appropriate measures, including legislation, to

modify or abolish existing laws, regulations, customs and practices which

constitute discrimination against women . . . ."12 All three international

standards are thus culturally neutral and universal in their applicability. They

provide a solid and legitimate political point of departure for women's rights

activists everywhere.

As for social-scientific research

to assess and compare the positions of women in different societies, a sixfold

framework of dimensions of women's status adopted from Janet Giele--a framework

that is quite consistent with the spirit of the Convention and the Nairobi

Forward--looking Strategies--can usefully guide concrete investigations of

women's positions within and across societies.13

●

Political

expression: What rights do women possess, formally and otherwise? Can

they own property in their own right? Can they express any dissatisfactions

within their own political and social movements?

●

Work and mobility: How do women fare in the

formal labor force? How mobile are they, how well are they paid, how are their

jobs ranked, and what leisure do they get?

●

Family: Formation, duration, and size:

What is the age of marriage? Do women choose their own partners? Can they

divorce them? What is the status of single women and widows? Do women have

freedom of movement?

●

Education: What access do women have, how

much can they attain, and is the curriculum the sane for them as for men?

●

Health and sexual control:

What is women's mortality, to what particular illnesses and stresses (physical

and mental) are they exposed, and what control do they have over their own

fertility?

●

Cultural expression: What images of women and

their "place" are prevalent, and how far do these reflect or determine

reality? What can women do in the cultural field?

This is a useful way of specifying

and delineating changes and trends in women's social roles in the economy, the

polity, and the cultural sphere. It enables the researcher (and activist) to

move from generalities to specificities and to assess the strengths and

weaknesses of women's positions. It focuses on women's betterment rather than on

culture or religion, and it has wide applicability. At the same time, it draws

attention to women as actors. Women are not only the passive targets of policies

or the victims of distorted development; they are also shapers and makers of

social change-especially Middle Eastern women in the late twentieth century.

Diversity in the Middle East

To study the Middle East and Middle

Eastern women is to recognize the diversity within the region and within the

female population. Contrary to popular opinion, the Middle East is not a uniform

and homogeneous region. Women are themselves stratified by class, ethnicity,

education, and age. There is no archetypal Middle Eastern woman, but rather

women inserted in quite diverse socioeconomic and cultural arrangements. The

fertility behavior and needs of a poor peasant woman are quite different from

those of a professional woman or a wealthy urbanite. The educated Saudi woman

who has no need for employment and is chauffeured by a Sri Lankan migrant worker

has little in common with the educated Iranian woman who needs to work to

augment the family income and also acquires status with a professional position.

There is some overlap in cultural conceptions of gender in Iran and Saudi

Arabia, but there are also profound dissimilarities (and driving is only one of

the more trivial ones). Saudi Arabia is far more conservative than Iran in terms

of what is considered appropriate for women.

Women are likewise divided

ideologically and politically. Some women activists align themselves with

liberal, social democratic, or communist organizations; others support Islamist/fundamentalist

groups. Some women reject religion as patriarchal; others wish to reclaim

religion for themselves or to identify feminine aspects of it. Some women reject

traditions and time-honored customs; others find identity, solace, and

strength in them. More research is needed to determine whether social background

shapes and can predict political and ideological affiliation, but in general

women's social position has implications for their consciousness and activism.

The countries of the Middle East and North Africa

differ in their historical evolution, social composition, economic structures,

and state forms. All the countries are Arab except Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan,

and Israel. All the countries are Muslim except Israel. All Muslim countries are

predominantly Sunni except Iran, which is predominantly Shi'a. Some of the

countries have sizable Christian populations (Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, the

Palestinians); others are ethnically diverse (Iran, Lebanon, Afghanistan); some

have had strong working-class movements and trade unions (Egypt, Tunisia, Iran,

Turkey) or large communist organizations (Egypt, Sudan, Iran, the Palestinians).

Others have nomadic and semi-sedentary populations (Saudi Arabia, Libya, Oman).

In almost all countries, a considerable part of the middle classes have received

Western-style education.

Economically, the countries of the region comprise

oil economies poor in other resources, including population (United Arab

Emirates [UAE], Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, Kuwait, Libya); mixed oil economies

(Tunisia, Algeria, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt); and non-oil economies (Israel,

Turkey, Jordan, Morocco, Sudan, Yemen). The countries are further divided into

the city-states (such as Qatar and the UAE); the "desert states"

(for example, Libya and Saudi Arabia); and the "normal states"

(Turkey, Egypt, Iran, Syria). The latter have a more diversified structure, and

their resources include oil, agricultural land, and large populations. Some of

these countries are rich in capital and import labor (Libya, Saudi Arabia,

Kuwait), while others are poor in capital or are middle-income countries that

export labor (Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia, Turkey, Yemen). Some countries have more-developed

class structures than others; the size and significance of the industrial

working class, for example, varies across the region. There is variance in the

development of skills ("human capital formation"), in the depth and

scope of industrialization, in the development of infrastructure, and in

standards of living and welfare.

Politically, the state types range

from theocratic monarchism (Saudi Arabia) to secular republicanism (Turkey).

States without constitutions are all Gulf states except Kuwait. Many of the

states in the Middle East have had consistent legitimacy problems, which became

acute in the 1980s. Political scientists have used various terms to describe the

states in the Middle East: "authoritarian-socialist" (for Algeria,

Syria, Iraq), "radical Islamist" (for Iran and Libya),

"patriarchal-conservative" (for Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Jordan), and

"authoritarian-privatizing" (for Turkey, Tunisia, Egypt). Some of

these states have strong capitalistic features, while others have strong

feudalistic features. In this book I use "neopatriarchal state,” adopted

from Hisham Sharabi, as an umbrella term for the various state types in the

Middle East.14 In the neopatriarchal state, unlike liberaI democratic societies,

Middle Eastern countries bind religion to power and state authority, resulting

in a situation whereby the family, rather than the individual, constitutes the

universal building block of the community.

In the Middle East there is a variable mix of religion and

politics. For example, Islam is not a state religion in Syria, whose

constitution provides that "freedom of religion shall be preserved, and the

state shall respect all religions and guarantee freedom of worship to all,

provided that public order is not endangered." Syria's Muslim majority

coexists with a Christian minority totaling about 12 percent of the population.

Christian holidays are recognized in the same way as Muslim holidays. Syria

observes Friday rest but also allows time off for Christian civil servants to

attend Sunday religious services. The constitution also guarantees women

"every opportunity to participate effectively and completely in political,

social, economic, and cultural life." Although women, especially in Syrian

cities, enjoy a degree of freedom comparable to their counterparts in the West,

it is difficult to reconcile women's rights with Quranic law, which remains

unfavorable to women with regard to marriage, divorce, and inheritance.

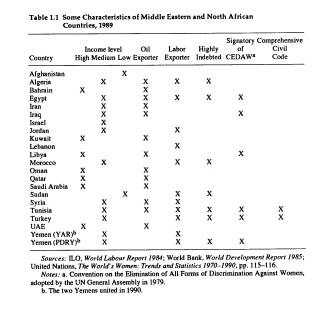

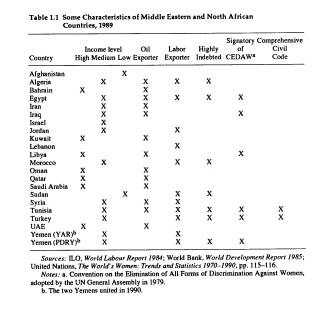

Table 1.1 illustrates some economic

characteristics of Middle Eastern countries, as well as juridical features

relevant to women. A key factor shared by all countries except Tunisia and

Turkey is the absence of a comprehensive civil code. Most of the countries of

the Middle East and North Africa are governed to some degree by Islamic canon

law, the Shari'a. (Israeli law is based on the Halacha.) Only in Turkey is there

a constitutional separation of church and state.

Given

the wide range of socioeconomic and political conditions, it follows that gender

is not fixed and unchanging in the Middle East (and neither is culture). There

exists internal regional differentiation in gender codes, as measured by

differences in women's legal status, education levels, fertility trends,

employment patterns, and political participation. For example, gender

segregation in public is the norm and the law in Saudi Arabia but not in Syria,

Iraq, or Morocco. In Iran, Egypt, Tunisia, and elsewhere, women vote and run for

parliament. In Turkey, the female share of certain high-status occupations (law,

medicine, judgeship) is considerable. Following the Iranian Revolution, the new

authorities prohibited abortion and contraception, and lowered the age of

consent to thirteen for girls. But in Tunisia contraceptive use is widespread,

and the average age of marriage is twenty-founts Afghanistan has the highest

rate of female illiteracy among Muslim countries, but the state took important

steps after the Saur Revolution of April 1978 to expand educational facilities

and income-generating activities for women. And, as seen in Table 1.2, women's

participation in government as key decision makers and as members of parliament

varies across the region.

If

all the countries we are studying are Muslim (save Israel), and if the legal

status and social positions of women are variable, then logically Islam and

culture are not the principal determinants of their status. Of course. Islam can

be stronger in some cases than in others, but what I wish to show in this book

is that women's roles and status are structurally determined by state ideology

(regime orientation and juridical system), level and type of economic

development (extent of industrialization, urbanization, proletarianization, and

positron m the world system), and class location. A sex/gender system informed

by Islam may be identified, but to ascribe principal explanatory

power to religion and culture is methodologically deficient, as it exaggerates

their influence and renders them timeless and unchanging. Religions and cultural

specificities do shape gender systems, but they are not the most significant

determinants and are themselves subject to change. The content of gender

systems is also subject to change.

A

Framework for Analysis:

Gender,

Class, the State, Development

The

theoretical framework that informs this study rests on the premise that

stability and change in the status of women are shaped by the following

structural determinants: the sex/gender system, class, the state, and

development strategy that operate within the capitalist world system.

Sex/Gender

System

A

useful definition of gender is provided by de Lauretis:

The

cultural conceptions of male and female as two complementary yet mutually

exclusive categories into which all human beings are placed constitute within

each culture a gender system, that correlates sex to cultural contents according

to social values and hierarchies. Although the meanings vary with each concept,

a sex-gender system is always intimately interconnected with political and

economic factors in each society. In this light, the cultural construction of

sex into gender and the asymmetry that characterizes all gender systems cross-culturally

(though each in its particular ways) are understood as systematically linked to

the organization of social inequality.16

The sex/gender system is primarily a cultural construct that is itself

constituted by social structure. That is to say, gender systems are differently

manifested in kinship-ordered, agrarian, developing, and advanced industrialized

settings. Type of political regime and state ideology further influence the

gender system. States that are Marxist (for example, the former German

Democratic Republic), theocratic (Saudi Arabia), conservative democratic (the

United States), and social democratic (the Nordic countries) have quite

different laws about women and different policies on the family.17

The

thesis that women's relative lack of economic power is the most important

determinant of gender inequalities, including those of marriage, parenthood, and

sexuality, is cogently demonstrated by Blumberg and Chafetz, among others. The

division of labor by gender at the macro level reinforces that of the household.

This dynamic is an important source women's disadvantaged position and of the

stability of the gender system. Another important source is juridical and

ideological. In most contemporary societal arrangements, "masculine"

and "feminine" are defined by law and custom; men and women have

unequal access to political power and economic resources, and cultural images

and representations of women are fundamentally distinct from those of men-even

in societies formally committed to social (including gender) equality.

Inequalities are learned and taught, and "the non-perception of

disadvantages of a deprived group helps to perpetuate those disadvantages."

18 Many governments do not take an active interest in improving women's status

and opportunities, and not all countries have active and autonomous women's

organizations to protect and further women's interests and rights. High

fertility rates limit women's roles and perpetuate gender inequality. Where the

state's policies and rhetoric are actively pronatalist, as with neopatriarchal

states, and where official and popular discourses stress sexual differences

rather than legal equality, an apparatus exists to create stratification based

on gender. The legal system, educational system, and labor market are all sites

of the construction and reproduction of gender inequality and the continuing

subordination of women.

Social change and societal

development come about principally through technological advancements, class

conflict, and political action. Each social formation is located within and

subject to the influences of a national class structure, a regional context, and

a global system of states and markets. The world-system perspective regards

states and national economies as situated within an international capitalist

nexus with a division of labor corresponding to its constituent parts--core,

periphery, and semiperiphery. As such, no major social change occurs outside of

the world context.' Thus, to understand the roles and status of women or changes

in the structure of the family, for example, it is necessary to

examine economic development and political change, which in turn are affected

by regional and global developments. As we shall see in the discussion of

women's employment, the structural determinants of class location, state legal

policy, development strategy, and world market fluctuations come together to

shape the pace and rhythm of women's integration in the labor force and their

access to economic resources. Figure 1.1 illustrates the institutions and

structures that affect and arc affected by social changes in a Marxist inform

ed world system perspective. The institutions arc embedded within a class

structure (the system of production, accumulation, and surplus distribution),

a set of gender arrangements (ascribed roles to men and women through custom or

law; cultural understandings of "feminine" and "masculine"),

a regional context (the Middle East, Europe. Latin America), and a world system

of states and markets characterized by asymmetries between core, periphery, and

semi-periphery countries.

Social change and societal

development come about principally through technological advancements, class

conflict, and political action. Each social formation is located within and

subject to the influences of a national class structure, a regional context, and

a global system of states and markets. The world-system perspective regards

states and national economies as situated within an international capitalist

nexus with a division of labor corresponding to its constituent parts--core,

periphery, and semiperiphery. As such, no major social change occurs outside of

the world context.' Thus, to understand the roles and status of women or changes

in the structure of the family, for example, it is necessary to

examine economic development and political change, which in turn are affected

by regional and global developments. As we shall see in the discussion of

women's employment, the structural determinants of class location, state legal

policy, development strategy, and world market fluctuations come together to

shape the pace and rhythm of women's integration in the labor force and their

access to economic resources. Figure 1.1 illustrates the institutions and

structures that affect and arc affected by social changes in a Marxist inform

ed world system perspective. The institutions arc embedded within a class

structure (the system of production, accumulation, and surplus distribution),

a set of gender arrangements (ascribed roles to men and women through custom or

law; cultural understandings of "feminine" and "masculine"),

a regional context (the Middle East, Europe. Latin America), and a world system

of states and markets characterized by asymmetries between core, periphery, and

semi-periphery countries.